Primeval Forest as a Refuge, Incubators as a Mission – the Life and Work of Dr. Božena Sernec Logar

Božena Sernec was born on 25 June 1914 into a distinguished upper-class family in the centre of Ljubljana. Her father, Dušan Sernec, was a renowned electrical engineer and politician. As the director of the Carniola Provincial Power Plants, he supervised the construction of the Završnica power plant near Žirovnica, so the whole family moved to Bled, where Božena attended elementary school. After her graduation from the Poljane Gramar School, she enrolled at the Faculty of Medicine in Graz. After Anschluss, she continued her studies in Prague, and finished in Belgrade, where she graduated in 1940. Following her degree, she interned at the General and Women’s Hospital in Ljubljana.

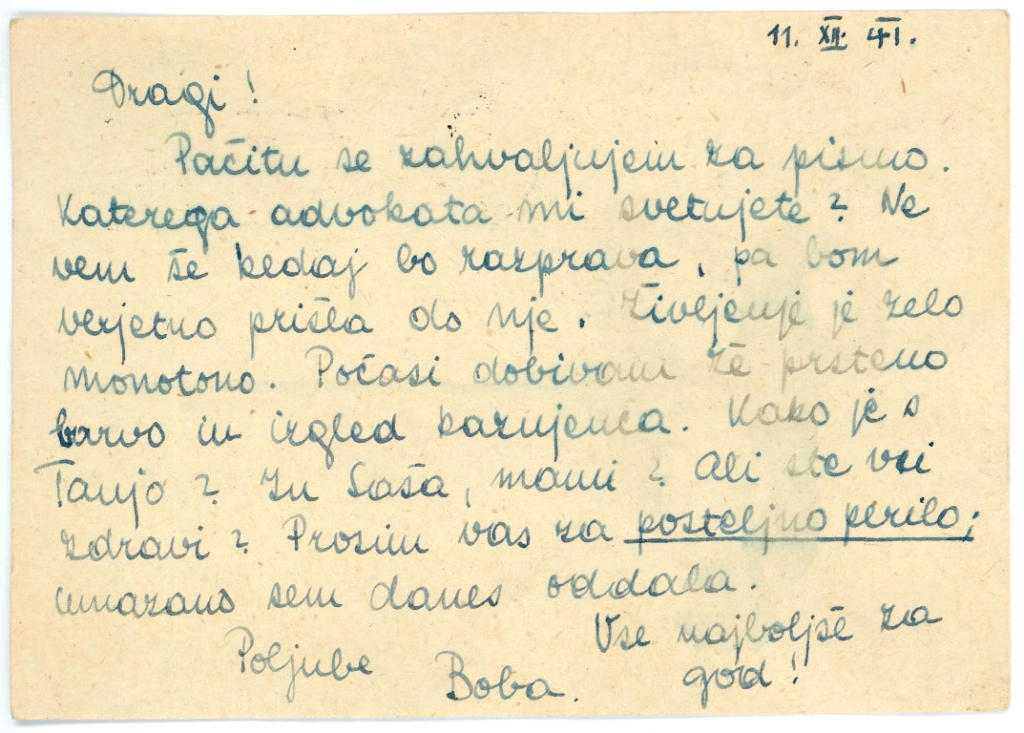

After the Axis powers invaded the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in April 1941, dr. Božena Sernec was one of the first doctors to join the resistance movement, barely a month after the occupation. At a meeting led by dr. Aleš Bebler, they discussed how to spread the ideas of the Liberation Front among doctors and to attract reliable colleagues to join the movement. One of her tasks was to collect clothing, medical supplies, and other equipment for partisans. She delivered them to Robert Golob’s storage facility on Wolf Street in Ljubljana. After she was betrayed, she was arrested on 27 November 1941 and imprisoned in the reformatory on Miklošič Road until the so-called Golob Trial. Despite her imprisonment, her thirst for knowledge did not wane—she continued to study in her cell.

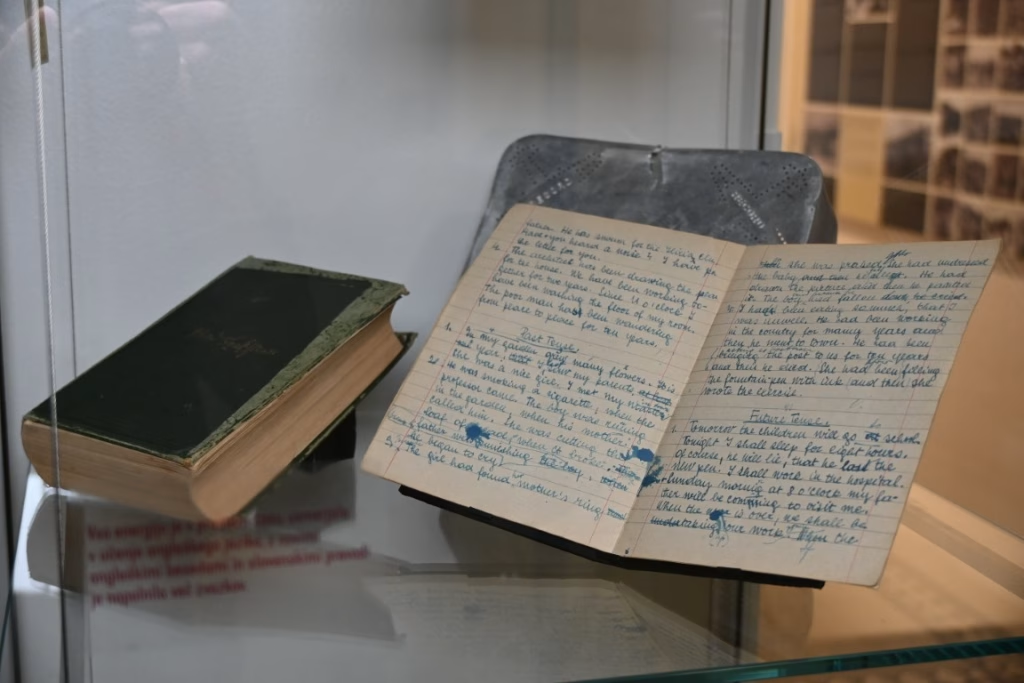

In February 1942, she was sentenced to three years of confinement in the Treia and Petriolo camps in the Italian province of Macerata. It was there that she met Maria de Lucia, an English teacher from Scotland. As rheumatism made everyday tasks and even personal hygiene difficult for her, Božena came to her aid, and in return, the Scottish woman helped her learn English. Božena filled notebooks with new words and even deepened her knowledge by translating Shakespeare’s works.

After the capitulation of the Kingdom of Italy in 1943, she, along with hundreds of Yugoslav and thousands od the British and American prisoners, left the Petriolo camp. She spent months hiding on farms at the foot of the Apennines, where she earned her living by treating ill famers. Among others, she also treated her compatriot Valentin (Tine) Logar, who suffered from dysentery. In the spring of 1944, they were forced to flee once again, since the farmers withdrew their hospitality out of fear of fascist violence.

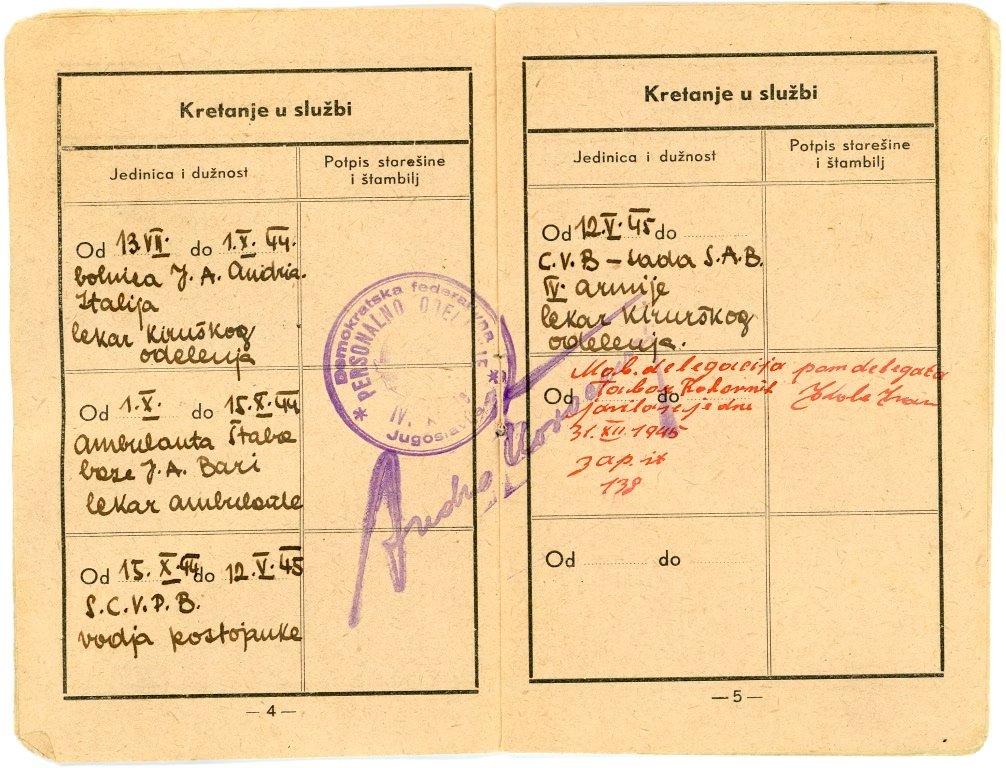

At the end of June 1944, Radio Svobodna Jugoslavija (Free Yugoslavia) appealed to refugees to report to Bari – Božena and Tine arrived there in early June by Allied lorries and trains. Tine worked in a partisan printing house while Božena was sent to the nearby town of Andria. The sanitary mission of the Headquarters of the National Liberation Army of Yugoslavia first sent her to the Mobile Military Hospital and then to the 64th English General Hospital, where she worked until October 1944. The hospital was based in a school and other offices; it was divided into internal medicine, surgery, and dentistry departments. Initially, American doctors were sceptical about the abilities and knowledge of their Slovenian colleagues, at least until they proved their resilience, resourcefulness, and competence. The Slovenian doctors earned the Americans’ respect after they successfully performed a demanding operation during which they removed a bullet from the spinal cord – a surgical procedure the American doctors had deemed impossible. Božena’s knowledge of English enabled her to effortlessly explain the course of the operation. She was so devoted to caring for her patients that she earned the disapproval of the nurses because she was constantly checking on their condition. Despite diligently caring for 40 Yugoslav patients at the Allied hospital, she wanted to return to her homeland.

In the autumn of 1944, the Sanitary Mission in Bari sent her to the liberated territory in present-day Slovenia – her airplane landed in the shelter of the Kočevje primeval forest in mid-October 1944. Two years earlier, the first partisan hospital was built there and led by dr. Pavel Lunaček – Igor; this was the foundation of the Slovenian Central Partisan Military Hospital, which connected 24 such hospitals. Initially, dr. Sernec worked in the hospital Zgornji Hrastnik that treated the most severely wounded partisans who needed surgery. The barracks, hidden deep in the primeval forest, seemed luxurious to her compared to those where they hid from the fascists in Italy. During the very first weeks after her arrival, she did not perform any surgeries, but with obstetrics. In late autumn 1944, dr. Sernec was transferred to the hospital Spodnji Hrastnik, taking over the leadership from dr. Božena Grosman – Vida. From 1 February 1945 until the end of the Second World War, she led the hospital Jelendol, and in March of that year, she successfully completed a month-long medical course in Črnomelj. The melting of the snow in the following months brought with it the anticipation of the end of the Second World War. Following the end of the conflict, Dr. Sernec was entrusted with caring for the most severely wounded partisans who were transferred from Trieste to the Military Hospital Mladika in Ljubljana. Furthermore, Tine also returned to their homeland and they got married in mid-June 1945.

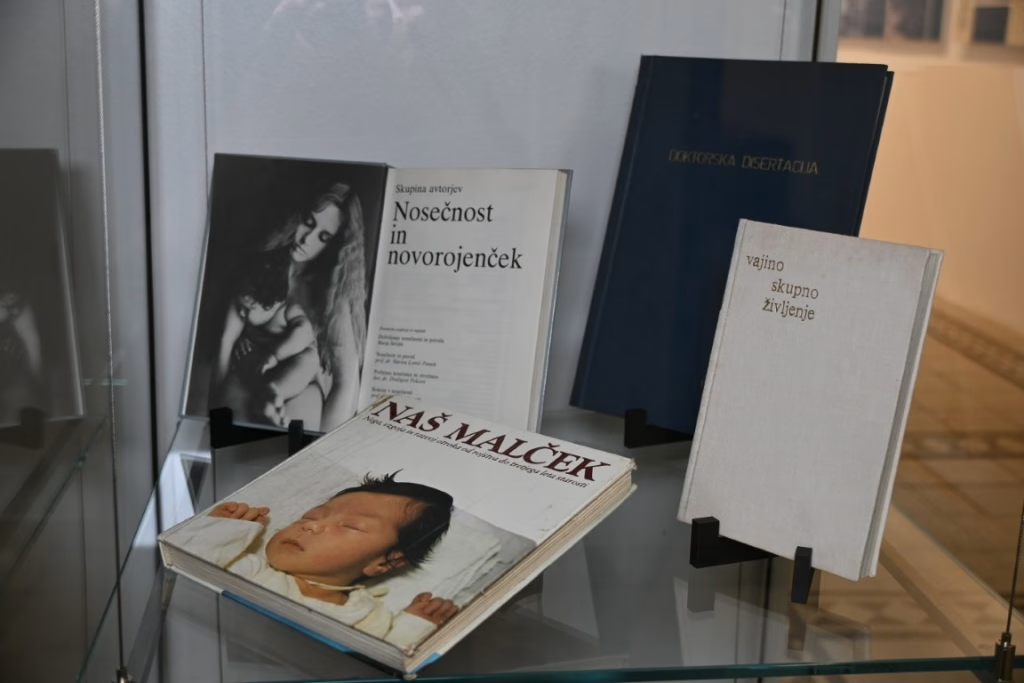

In the autumn 1945, she was demobilised and started working at the Pediatric Clinic in Ljubljana. Two years later, she continued her professional career in the Neonatology Department of the Gynecology Clinic in Ljubljana, where she devoted herself to treating hypoxia in newborns and acquiring modern incubators to replace the wooden ones. In the 1960s and 1970s, she focused on long-term international scientific research projects, drawing on the English she had acquired during her confinement in Italy. In 1970, she received her doctorate from the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Ljubljana with a dissertation entitled Hypoxia neonati, and in 1998, her lifelong work in Slovenian paediatrics was recognised when she received the Derč award.

Her post-war life was marked by tireless care for newborns despite the constant surveillance she was subjected to, especially after her husband was sent to Goli Otok (an island in present-day Croatia with a labour camp where political prisoners were sent) during the Yugoslav conflict with the Cominform, leaving her alone with a toddler and a baby. During this difficult period, Dr. Pavel Lunaček, director of the Gynaecological Clinic, took her under his wing, and she became even more committed to her mission.

Dr. Božena Sernec Logar died of heart failure on 11 December 1997; however, her legacy lives on – as the heritage of a physician who cared for wounded partisans deep in Kočevje primeval forest and later helped lay the foundations of Slovenian neonatology.